Lessons From The Hermitic Order of the Golden Dog

On solitude, safety, freedom and the catharsis of burning it all down

When I first joined Substack, I desperately wanted to be seen as a serious writer. Well, technically, at first, I was just ranting into the void, never thinking anyone would ever listen or care. There was something cathartic about it, like keeping a journal no one would read, maybe discovered years later by accident before being tossed in the trash. But then, something strange happened. People actually listened. The void gazed back. That's when I wanted to be taken seriously. As a political thinker, philosopher or something like that. A modern Burnham or a less annoying Zizek. I've read books, you see. Grown-up books on politics, history, psychology, serious literature- that's what you're supposed to write about when you're a serious writer. But people didn’t seem to care as much when I waxed poetic about politics. At first, I was disappointed. But there was a silver lining- People did care when I wrote about strange, esoteric subjects like hikikimoris, the Unabomber or Venture Bros. And hey, at the end of the day, I suppose I don't really care. As long as people are reading, I'm flattered. In the world of social media and writing, you are what people see you as and you’re lucky if anything you do resonates, even if it wasn’t necessarily what you set out to do. So, to that end, here's an essay about how a baby show kept me from wanting to kill myself.

Adventure Time ran on Cartoon Network from 2010 to 2018. The show stars Jake the Dog and Finn the human and follows them in their adventures ranging from the whimsical to the surreal. Finn and Jake, best friends and brothers, live in a post-apocalyptic world that's equal parts Dungeons and Dragons, Mad Max, Candy Land and Lovecraftian horror. Adventure Time also gets genuinely strange as the series goes on, dealing with themes of depression, identity and confronting the absurd and disturbing. The show also has overt occult themes and imagery, even bordering on cosmic horror at times. I have a theory that Zoomers are so depressed because they grew up on shows like Adventure Time and Steven Universe, melancholic, ennui-laden fare made by SSRI-addled millennials, but that’s neither here nor there. Originally, I first encountered Adventure Time as many a stoned early 20-something did- merely looking for some light entertainment and extended adolescence. A decade ago, I enjoyed it for what it was, but life has since caught up with me and I hadn’t watched it or given it any thought for years. But by pure coincidence, I recently found myself watching an episode playing in a doctor’s office waiting room. It was an episode that I had a vague memory of, but this time something about it felt different.

The episode begins with Jake encountering his other brother Jermaine in a dream. Where Jake’s dreams are filled with rainbow unicorns and boundless freedom, his brother, Jermaine, dreams of being trapped in a small, gray box. When Jake enters Jermaine’s prison, there’s a palpable tension between the two that anyone with estranged family members can immediately identify. Polite, but terse. The awkward interaction between people who were once extremely close but have grown apart. The discordance between the memory of closeness clashing with the reality of the present distance. Jermaine is clearly annoyed by his care-free younger brother for interrupting his solitude, but Jake persists in trying to cheer him up, unaware or unbothered by Jermaine’s annoyed ambivalence. Jake suggests meeting up in the waking world and Jermaine agrees, half-heartedly. When he wakes up, Jake convinces Fin to visit their brother even though Fin is hesitant due to Jermaine’s standoffish demeanor, but they make their way to see their brother in the waking world.

The pair make their way to their childhood home, where Jermaine now lives alone. Unlike his magical, free-spirited brothers, Jermaine is a non-magic dog who has chosen- perhaps unconsciously- to imprison himself in a life of obligation. He’s become the reluctant caretaker of their father Joshua’s legacy: a house cluttered with cursed artifacts, arcane relics, books, hard drives and the emotional residue of a bygone era. The home is under constant siege by demons, held back only by a ring of shaman blessed, sage-infused salt. Inside, a demon named Bryce lurks in the basement, kept at bay by a spell bound to a cassette tape played on a loop by a stuffed bear named Bobosuza. If Jermaine ever forgets to flip the tape, Bryce reminds him, he’ll be eaten from the bottom up. Jermaine is trapped between the demons of the outside world and the demons inside; with only the artifacts he protects for company.

Far from a warm and emotional reunion, the relationship between Jermaine and his estranged brothers is tense. While Jake and Finn rampage through their childhood home, interacting with the objects their father left behind like living memories, Jermaine reacts as a grumpy museum curator would to intrepid children stepping past the red velvet rope- seeing his brothers as trespassers on the memories that they share but he alone has to guard. Jermain scolds them for their irreverence, saying it’s his duty to protect their home and their father’s legacy while they get the privilege of living an unbound life. Jermaine lives like a monk in a crumbling temple, trapped by duty and haunted by responsibilities he never asked for. He’s a hermit in the truest archetypal sense: wise, vigilant, self-disciplined- but also isolated, burdened, and bitter. Meanwhile, Finn and Jake live with childlike freedom, unmoored from legacy or consequence. They see Jermaine’s stress, but he insists he’s fine. He even calms himself by reciting Greek numerals, as if logic and routine can fend off the chaos clawing at his door.

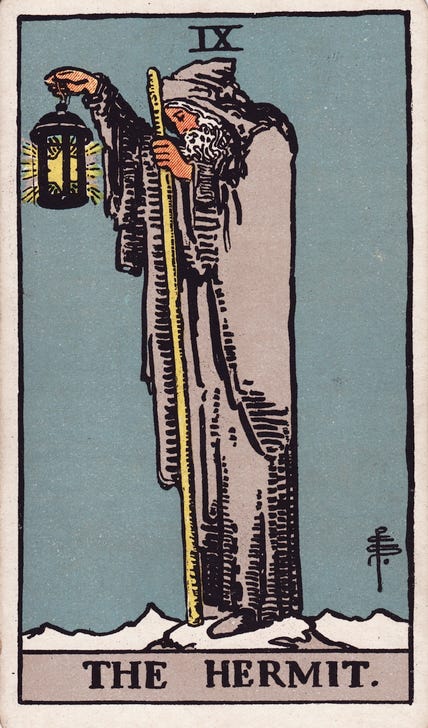

Jermaine embodies the classic archetype of The Hermit in tarot: a figure who seeks wisdom and understanding through introspection and solitude. Like the Hermit, Jermaine has withdrawn from the chaotic, unpredictable world around him, choosing instead to guard his father’s legacy and the artifacts that hold deep personal meaning. His life is one of quiet reflection, steeped in the knowledge of his father’s adventures, and the careful maintenance of the artifacts that tell the story of a world he once knew. In a way, Jermaine is a keeper of wisdom- he understands the past deeply, and in his solitude, he has cultivated a kind of quiet reverence for that knowledge. This resonates with me deeply because, like Jermaine, I’ve often turned to books, music, and films as a way to find understanding. There is something deeply comforting in the pursuit of knowledge, knowing that there are others who have thought deeply about the world and its complexities. That you’re not alone, and there have been countless others across human history and cultures that have thought and felt as you do. This desire to understand, to see things more clearly, is something I’ve always strived for. Like the Hermit, I believe there’s value in seeking answers in solitude, away from the noise and distractions of the outside world. There’s wisdom in taking the time to reflect, to allow one’s thoughts to settle, and to uncover insights that might otherwise remain hidden. Jermaine’s journey speaks to the power of reflection and wisdom, which, at its best, helps us understand ourselves and our place in the world.

But there is also a dark side to The Hermit. The urge to withdraw, to collect knowledge, and to focus on the past can lead to isolation- a disconnection from the present, and from the world outside. Jermaine is locked in a self-imposed prison, surrounded by artifacts of a bygone age, constantly fending off demons that represent both real and metaphorical threats. His life is one of perpetual vigilance, unable to move forward or connect with the world around him. He clings to the past, guarding his memories from a present that they are incompatible with, but in doing so, he never truly engages with the world in front of him. This is something I’ve always struggled with and in that way, I deeply relate to this cartoon dog. I’ve always sought refuge in isolation. Even as a child, I was a loner who preferred my books or Legos to the company of most others. While not antisocial, I always struggled and continue to struggle to this day to make friends and relate to people. When the world feels overwhelming, it’s easier to close myself off, to collect things- books, records, films- as a way to make sense of the chaos. But when I do that, I’ve found myself becoming disconnected. Isolated. The knowledge I crave can sometimes feel like a shield, a way to protect myself from engaging with the outside world. It’s like building walls around me, not realizing that in trying to keep the world out, I’ve also kept myself in. Just like Jermaine, I’ve felt the weight of this isolation, the sense of being trapped by my own desire for safety and certainty. I have spent a lifetime accumulating knowledge of history, politics, psychology and literature as if categorization of the world could give me control of it. The more I cling to what I know, the more I retreat from the possibility of living fully, of stepping into the uncertainty of the present. The darker side of The Hermit is this: when introspection turns into avoidance, when knowledge becomes a prison instead of a doorway to connection. It’s a reminder that while it’s valuable to seek wisdom, we must also be willing to face the world as it is, to step outside the walls we’ve built and engage with the unknown.

More and more, I find myself looking at the world and feeling disconnected from it, as if I’m watching life unfold from a distance- like an observer instead of a participant. The future feels increasingly bleak, and I can’t seem to picture a version of it where I fit in. For those who seek order and control through a sense of understanding the world, the chaos of an uncertain future feels like an existential threat. Where the future once felt boundless and like opportunities were endless, it now feels like a rapidly shrinking horizon. In my writing, I try to project some sense of positivity. On my podcast, I always end by asking the guest what makes them feel hopeful for the future. I know some may find it saccharin, and maybe it is. Honestly, I first asked the question because I didn’t know what I was doing, and it was a spontaneous way to fill airtime. Then, it became a comforting routine, a way of adding structure to conversations, another layer of control. But as time went on, these answers became points of light in a dark sky for me. By nature, I am a deeply pessimistic person. The future increasingly feels like a foreign country, and one where I don’t belong. So, when I ask for what makes people hopeful for the future or try to find light in the darkness with my writing, know I am trying to convince myself more so than I am the reader. Because increasingly, I look at the world around me and towards the future and I don’t see much that I like. More and more, I would rather shut out the world than engage with it.

I’ve come to realize that this attitude is a form of passive suicidal ideation- not a desire to end my life outright, but a deep longing to drop out of the world entirely, to let it drift by without me. To be alive, but dead to the world. It’s like being a hermit sealed away in a tower, watching the world burn from behind thick stone walls, not with fear or urgency, but with a cold sort of detachment. I don’t want to kill myself actively, it’s more about stepping back so far that life no longer reaches me. In retreating into solitude, I feel like I regain some measure of control in a world that feels increasingly chaotic and alien. Surrounding myself with familiar objects- books, artifacts, fragments of a more enchanted time- gives me a sense of order, even if it means becoming a ghost in my own life. Sometimes I want to die- not violently, not dramatically- but quietly, subtly, through withdrawal. Sometimes I think I want to die because I’m just tired. Somewhere along the way, I stopped finding joy in the things I used to love. The future stopped feeling like a thrilling adventure and started feeling like endless repetition. Life became less like a story unfolding and more like a video game I’ve played too many times- where I’ve died just before the boss fight and now have to replay the same tedious level over and over again. I know all the jumps, all the timing, but it no longer excites me. The magic is gone, and now I only see the code, the mechanics, the dead loops. I don't hate the game- I just don't want to play anymore. And so, I don’t rage-quit. I simply reach over and turn off the console. Not out of despair, but out of weariness. A desire to stop pretending. A desire to reclaim even that final, quiet choice- to be left alone, untouched by the noise of the world.

And this attitude, this failure, has hurt people that I love. When I’m afraid, stressed or uncertain, I withdraw rather than lashing out. I will turn to self-destructive patterns, falling back on abusing substances and immersing myself in knowledge dark and arcane, as corrosive to my spirit as the bourbon is to my liver. I have pulled away from family, friends, loved ones. I’ve hurt the people I love, my precious few close relationships, because of this tendency to isolate myself. I’ve lost friends I could have kept if I had been able to step outside my walls and ask for forgiveness or show empathy. I’ve missed important life events, not been present when people needed me because I was locked away in my tower, so to speak. And like there is the trope of the wise and kind hermit, there is the dark inversion. The evil sage, the malevolent force who has looked too deeply into the darkness of the world and allowed it to change him in a way that can never be reversed. Someone who has seen too much of the world from a distance and has not had others in his life to temper that cynicism. To be filled not with fiery anger, but a cold, cynical detachment and disdain. And that’s where I increasingly have found myself- poisoning my mind and body because of fear of the outside world. A long, slow suicidal death march. Building my own tomb, a mausoleum of isolation.

This sense of weary disconnection, of choosing solitude and knowledge as a way to feel in control amidst chaos, comes full circle in Jermaine. When Finn and Jake arrive, their carefree presence disrupts more than just the mood. In a moment of characteristically childlike obliviousness, they break the protective salt seal around the house- Jake uses some of it to make fried rice. But that seal was what kept the demons at bay. Without it, chaos floods in, breaching the seal that gave Jermain his sense of control and safety. The demons breach the home, and though the trio manages to defeat them, the damage is done- not just to the house, but to Jermaine’s fragile sense of order. Something in him snaps. He unloads years of resentment, accusing Jake of always being the favorite, of gallivanting through magical adventures while he was left behind to clean up their father’s mess. The argument boils over until Finn and Jake, perhaps for the first time, hold a mirror up to Jermaine. No one forced him into isolation. No one told him to be the martyr, the watchman of their father’s decaying legacy. That was a choice- a prison he built himself, brick by brick, under the illusion of duty and control. In the scuffle, the house catches fire. Finn and Jake, eager to make amends, offer to help save it. But Jermaine, finally seeing it for what it is, declines. “Let it burn” he says, with a calm born not of defeat, but of release. “I think It’s allright”. And in that moment, he chooses freedom over control, the unknown over the suffocating safety of solitude.

In the final moments of the episode, the message lands with quiet clarity. As the house smolders and the illusions of control and duty collapse, something unexpected happens: Bryce, the demon long kept at bay by a looping tape spell, escapes. But instead of attacking, he confronts Jermaine in a moment that’s strangely calm. The years of fear and tension between them dissolve- not into friendship, exactly, but into familiarity. They’ve come to know each other, adversary and warden, almost like roommates or an old, married couple. And Jermaine, no longer clinging to rituals and salt rings and the burden of preservation, doesn’t panic. He faces Bryce not as a jailer but as an equal. It’s a small but profound shift: in relinquishing control, Jermaine gains clarity. The demon loses its power not because it’s defeated, but because it’s finally seen in the light of day. And that, I think, is the quiet genius of the episode. It shows that healing doesn’t always come from winning or fixing everything, but from the willingness to see the world as it is- to accept its unpredictability, to let go of the past, and to step outside, even when it’s terrifying. In that burned-out house and that broken salt ring, there’s a kind of freedom. A permission to move forward, even if you don’t feel entirely ready.

Watching Jermaine, I saw more than just a surreal episode of a “kids’ show.” I saw a mirror. A reflection of my own tendency to retreat, to build walls out of books and rituals, hoarding knowledge, out of alcohol and apathy. Like Jermaine, I’ve told myself that my isolation was a noble burden- something I had to carry, a role I was assigned. But no one assigned it to me. I chose it. I created the prison, one carefully arranged artifact at a time. And like him, I kept the demons at bay with salt circles- routines, distractions, escapes- anything to keep the fear and uncertainty from getting too close. Apathy of and disdain for the world does not set you above it, only apart from it. But fear doesn’t vanish just because you shut the door. It waits. It whispers. It grows stronger in the silence.

I’ve come to realize that staying isolated, numb, and disconnected is its own slow death. Not a dramatic one, but a passive fading. The spiritual equivalent of slitting your wrists and slowly bleeding out in a warm bath. The books I read, the drinks I pour, the comfort I find in repetition- none of these things are inherently bad. But when I use them to hide, to keep life at a distance, they become just another wall. Just another way to say “no” to living. And this isolation destroys your ability to enjoy life. And the walls you build to keep yourself safe will also keep people you love away.

Like Jermaine, I will have to make a choice. The world is changing. It’s overwhelming. It’s not what I expected, and I don’t know what my place in it will be. But I do know that staying hidden won’t protect me. It just keeps me frozen. At some point, I will have to step out of the tower, let the fire burn through what no longer serves me, and face whatever comes next- not with confidence, but with honesty. Not with control, but with presence. So, I’ve decided things are going to be okay. They’re’ going to be different, they will be scary, but they will be okay.

It will be what it will be. I won’t understand all of it. I won’t like all of it. But it will be real. And if I can let go of the illusions, the salt lines, the looped tapes keeping my demons contained, maybe I’ll finally see them for what they are. And maybe, just maybe, they’ll be less scary once I stop running.

The world is still strange. Still burning. But I think I’m ready to open the door.

i can't speak to the state of the world, but so long as i walk through this world you'll have a place in it, as my friend, who sees the absurdity, whose concerns come from a place of deep, irreducible empathy, and who is too smart and educated to accept any of the simple (wrong) answers.

never obligation, never expectation, just, the place you sit on the overpass when we throw rocks at passing cars will always be yours, and there'll always be a drink waiting for you at your spot at the table.

i hope life treats you well friend, and i hope the parts that don't are things you know you can overcome, because you can.

It’s funny this morning my teenage daughter decided to engage in some nostalgia and watch cartoons and I walked into the living room and she was watching Adventure Time! A few minutes later I saw your post:)

It’s great, and I appreciate where you’re coming from. What I read in this piece is someone who knows that a hermit can at times be isolated from the world but one whose greater concern is making meaning from the chaos of it, which is really what it’s all about isn’t it?